You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters

- Thread starter mikelove

- Start date

rizen suha

状元

it would seem so, however, the answer by ash left me with doubts.Don't Ash's, @Ash , answers to Shun's, @Shun, similar question address this?

https://www.plecoforums.com/threads/outlier-dictionary-of-chinese-characters.4703/page-15#post-42428

John Renfroe

进士

you say:

>>藏 began to be used via sound loan to represent “to store.” 贓 zāng “goods obtained by illegal means”and 臟 zàng“internal organs”are both meanings extended from “to store.”<<

i was wondering if the dictionary will include this kind of analysis, going beyond stating that 藏 is a sound component.

Yes.

And to answer your previous concern:

as a work in progress, it would perhaps be preferrable to mark information that is pending research or verification as such.

Anything that only has a component breakdown (A is a sound component, B is a meaning component) with no further explanation of the components ("B is a meaning component which means X and points to the original meaning Y", etc.) is incomplete and pending further research. That is, we know that the components serve the function listed, but it's possible that upon further research, we may find that it also serves another function. About 1200 characters currently have entries like that (including 臟), and 500 characters have more complete entries (adding another 250 in the next update for a total of 750). If the available evidence for those characters suggests that a breakdown needs to be amended (that is, for example, if a sound component also turns out to carry semantic value), we will amend it.

Last edited:

Ash

进士

Don't Ash's, @Ash , answers to Shun's, @Shun, similar question address this?

https://www.plecoforums.com/threads/outlier-dictionary-of-chinese-characters.4703/page-15#post-42428

Yes, you are correct. Thanks! As far as 贓 and 臟 specifically, it would end up in the Expert Edition data. It's actually a good illustration of characters being derived by sound as opposed to by meaning.

rizen suha

状元

In fact, all components are forms (Gestalten), otherwise they couldn't be perceived by our sense of sight. What you call "form components" is what semioticians call "icons". I'd use "iconic components" instead of "form components".Our system explains characters in terms of their functional components, i.e., the parts of a character that are doing something in that character. Each component has 3 attributes: form, sound and meaning. There are 4 types of functional components: Form components, Meaning components (these two are collectively called semantic components), Sound components and Empty components. Each time these words appear in the dictionary, there is a link to an explanation of what they are. Understanding these 4 types is crucial!

By the way, what function do "empty components" perform?

Last edited:

Ash

进士

"Iconic component" is a good name, but there is one disadvantage to it. Each of the component types, strictly speaking, are roles a component can play in a character, not the "nature" of the component. What is a form component in one character, may be a meaning, sound or empty component in another. These types are derived from one of the three component attributes: sound, meaning and form. The reason we call them "form" components is that their meaning as it is expressed in a given character is derived from the form itself or as you call it its "iconic"ness. It does not mean that other component types don't have a form (in the same way that calling a component a sound component does not mean other components don't have a sound), but rather it is the form attribute that is emphasized. Calling it a "form component" keeps the tie to "form" (one of the three attributes) more obvious. One advantage that "iconic component" has though is that it would probably need less explanation. Thanks for the suggestion. It's something to consider.In fact, all components are forms, otherwise they couldn't be perceived by our senses. What you call "form components" is what semioticians call "icons". I'd use "iconic components" instead of "forms components".

By the way, what function do "empty components" perform?

"Empty component" is short for "empty form component," since the meaning and sound normally associated with that component are not used. Take 京 for instance. All components in 京 are empty. The 亠 has nothing to do with the sound tóu or the meaning "lid," the 口 has nothing to do with the sound kǒu or the meaning "mouth; entrance," the 小 has nothing to do with the sound xiǎo or the meaning "small." 京 is just a depiction of a tall building. Here, the empty components are substituting for earlier (and different) forms. When this character was invented, they did not use the oracle bone forms of 亠, 口 and 小. It was just a depiction of a tall building.

Another origin of empty components is deriving one character from another. Characters derived in this way are called 分化字. 高 was formed by adding a 口 to 京. The job of the 口 that was added was merely to distinguish 高 from 京, not to give the sound kǒu or the meaning "mouth; entrance." 京 was used to mean "tall building," "capital (the place where tall buildings are)," "tall," etc. 高 was created to represent the meaning "tall" and thereby to lower the number of possible meanings 京 could have in a given text.

In summary, empty components do not give a sound or meaning. They exist mostly due to character corruption (as with 京) and via the process of inventing new characters by adding a distinguishing mark (分化符) (as with 高).

Thank you, Ash. Can be then say that the function of empty components is to distinguish certain characters from others? If the answer is yes, do empty components always have this function? Maybe their function has come to be sometimes distinctive, and sometimes just expletive.In summary, empty components do not give a sound or meaning. They exist mostly due to character corruption (as with 京) and via the process of inventing new characters by adding a distinguishing mark (分化符) (as with 高).

Last edited:

Ash

进士

No. A major source of empty components is character corruption.Thank you, Ash. Can be then say that the function of empty components is to distinguish certain characters from others? If the answer is yes, do empty components always have this function?

Ex. 是 shì is composed of 旦 + 止 zhǐ. It's not clear what role 旦 plays, but this is not 旦 dàn "dawn" (we know this because the ancient forms are different). So, in 是, 旦 is empty. It does not give a sound or meaning.

Ex. 前 qián, the "䒑 over 月" part was originally 歬 qián, the sound component (and this form was used in earlier times to represent "front", but that doesn't matter here). The 月 here is not "moon" and doesn't give the sound yuè. 䒑 does not give the meaning "grass" or the sound cǎo.

It's best to understand "empty component" as "this component does not give a sound or meaning {in this character}." But something that is an empty component in one character, may be a sound, meaning or form component in another.

Like 旦 is empty in 是, but is a sound component in 但.

Which is the same as saying "this component has no function {in this character}."It's best to understand "empty component" as "this component does not give a sound or meaning {in this character}."

So unless we see in it an expletive function, the empty component X is a functional component with no function in character Y, that's why it's called empty. (Component X functions as a form/meaning/sound/empty component in character Y)There are 4 types of functional components: Form components, Meaning components (these two are collectively called semantic components), Sound components and Empty components.

Last edited:

Ash

进士

I wouldn't say that. If it had no function, then removing it would have no effect. In the case of a corrupted component, it's basically a place holder or substitute. In the case of being a distinguishing mark, it's distinguishing two characters. What these two have in common is that their respective components don't express sound or meaning. We grouped them into one category to keep the number of categories to a minimum. This framework is aimed at understanding the character for the purpose of learning and remembering. If they were paleographic categories, there would be a lot more of them. I would think the average learner does not want to be burdened with having to learn a lot of categories (especially since knowing them doesn't help you learn or remember any better). Understanding that a given component does not express a sound or meaning is sufficient to understand how that character works. It's not necessary, and probably harmful for many people, to know all of the paleographic details.Which is the same as saying "this component has no function {in this character}."

Ex. The story of 前 qián "front; ahead." The earliest form of what would later become 前 is composed of 止 "foot" and either 凡 "a (washing) pan" (or a simplified version of 桶 "bucket"), meaning "to wash one's feet" (this word is now written 湔 jiān). The thing on the bottom got corrupted into 舟, forming 歬. Because the sound of 歬 qián sounded like the word for qián "front; ahead," it started being used via sound loan to represent that meaning. Later, a word jiǎn "to cut off" needed a character, so someone added 刂 "knife" to 歬 qián to create 歬+刂. 歬+刂 got corrupted into 前 (止 → 䒑 and 舟 →月). Since 前 jiǎn "to cut off" sounded similar to qián "front; ahead," they started writing "front; ahead" as 前. In order to write jiǎn "to cut off," they needed a new character, so someone added another knife 刀 to the bottom of 前, creating 剪 (which now has 2 knifes: 刂 and 刀). So, 前 (originally "to cut") now means "front; ahead." 剪 means "to cut" and has two knives.

If we were to tell such a story in our dictionary for the average person, they would be super annoyed and probably confused. It's a very confusing story. It doesn't help anyone learn 前. Knowing that 䒑 and 月 are empty components allows you to learn 前 without having to follow or even know about that whole story. Knowing that 刂 originally gave meaning, however, is actually helpful (because it tells you why 刂 is there in the first place), but you can know that without following the real story. The needs of a learner are far different than those of a paleographer.

The real value of our dictionary is in this 3 attributes, 4 type of functional components system. It is a simple, unified way of explaining all characters without dragging anyone into complex, paleographic details. The ancient forms are great, but except in cases where it helps you see the connection to the modern form (like for 監, seeing the ancient form is super useful), they are fun, but not strictly speaking necessary for learning.

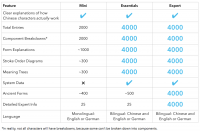

That's why we have an Expert edition. A place to put all of those interesting, gory details and ancient forms such that it doesn't detract from learning. The Essentials data is called Essentials because it's stuff you have to know.

Ash

进士

I just now saw this comment. I would say it this way:So unless we see in it an expletive function, the empty component X is a functional component with no function in character Y, that's why it's called empty. (Component X functions as a form/meaning/sound/empty component in character Y)

Empty component X is a functional component that does not express a sound or a meaning in character Y, which is why it is called empty.

Two other terms that might help:

Empty form - a form that has no sound or meaning connotations. Ex. the 大 in 莫 has the form 大 due to an earlier 艸(艹) "vegetation" corrupting into 大, not because it gives the sound dà, the form "front view of a standing person," or the meaning "big." In 莫, 大's form is empty.

Full form - a form that has sound and/or meaning connotations. Ex. the 大 in 美 has the form 大 because it is being used here as a depiction of the front of view of a standing person. In 美, 大's full form is used.

When an empty form is used in a character, it is called an empty component.

When a full form is used in a character, it is called a form component.

Hello, Ash. Just to confirm that I've understood all your explanations correctly.I just now saw this comment. I would say it this way:

Empty component X is a functional component that does not express a sound or a meaning in character Y, which is why it is called empty.

When an empty form is used in a character, it is called an empty component.

When a full form is used in a character, it is called a form component.

When an empty form is used in a character, it is called an empty component (whose function may be either that of a place holder or to distinguish the character in question from a similar one).

When a full form is used in a character, it is called a form component, a meaning component (both semantic) or a sound component, depending on whether its function is to stand for a meaning or a sound.

Thank you again, Ash. I apologize for taking up so much of your time.

Last edited:

Ash

进士

No worries. Yes, that is basically correct. The only thing I would add is that sometimes a component can be both a semantic (either form or meaning) component and a sound component. There's a lot on that topic in this thread if you're interested.Hello, Ash. Just to confirm that I've understood all your explanations correctly.

When an empty form is used in a character, it is called an empty component (whose function may be either that of a place holder or substitute).

When a full form is used in a character, it is called a form component, a meaning component (both semantic) or a sound component, depending on whether its function is to convey a meaning or a sound.

Thank you again, Ash. I apologize for taking up so much of your time.

I find the following specially reassuring:The only thing I would add is that sometimes a component can be both a semantic (either form or meaning) component and a sound component. There's a lot on that topic in this thread if you're interested.

That's why I tend to be very cautious when I read explanations as the following (taken from Post-Lingual Chinese Language Learning. Hanzi Pedagogy Palgrave Macmillan UK (2017), p. 69):Thirdly, I'm not opposed to the idea of sound components expressing a meaning, but I'm only going to make decisions based upon evidence.

"By structuring the world into square Hanzi, Chinese people in their own way address epistemology by this method of representation of “what the world is”. Take “疆” (Jiang: border) as an example. The right component of this Hanzi is the intertwining of roads (lines) and fields (squares) and the left section contains a bow facing towards the land. In ancient wars, a bow would have been the most common weapon. This Hanzi denotes that a country’s territory is defensible/defendable and war might be the consequence for crossing the border or invading a peaceful civilian life of another country."

Ash

进士

Yes, you are right to be skeptical for many reasons.That's why I tend to be very cautious when I read explanations as the following (taken from Post-Lingual Chinese Language Learning. Hanzi Pedagogy Palgrave Macmillan UK (2017), p. 69):

"By structuring the world into square Hanzi, Chinese people in their own way address epistemology by this method of representation of “what the world is”. Take “疆” (Jiang: border) as an example. The right component of this Hanzi is the intertwining of roads (lines) and fields (squares) and the left section contains a bow facing towards the land. In ancient wars, a bow would have been the most common weapon. This Hanzi denotes that a country’s territory is defensible/defendable and war might be the consequence for crossing the border or invading a peaceful civilian life of another country."

1. Chinese characters weren't square when 疆 was invented. That didn't happen until about 2000 years later.

2. It's very doubtful that the square shape of a Chinese character has anything to do with how the Chinese see the world today let alone in ancient times. Very, very few ancient Chinese could read or write anyway.

3. Individual Chinese characters were invented to solve very real, practical problems: i.e., representing a spoken word (word = sound + meaning combination). Any explanations that try to attribute deep philosophical connotations into a single character should be viewed with harsh skepticism and the burden of proof lies on the person making such claims.

Ex. 王 wáng "king." I saw an explanation that says that the top stroke is heaven (天), the middle stroke is the Earth (地) and the bottom stroke is people (人). The horizontal stroke that connects Heaven, Earth and humans is the king.

Seeing an explanation like that immediately raises suspicion. According to modern paleography, the character 王 was originally a depiction of a battle axe. Weapon = symbol of power, holder of power = king. Mao said, "Power comes out of the barrel of a gun." That's very concrete. Note how even in Mao's statement, "gun" doesn't really mean "gun" as much as it means "weapon." He's not saying to not have cannons or bombs. He's saying whoever has the weapons has the power.

4. "bow facing towards the land" The direction here doesn't matter at all.

5. "a bow would be the most common weapon" Seriously?! I'm thinking spears and swords would far out number bows. I'm not an expert, but a bow being the most common weapon simply makes no sense.

6. "This Hanzi denotes that a country’s territory is defensible/defendable and war might be the consequence for crossing the border or invading a peaceful civilian life of another country." See how much meaning they are trying to attribute to one character's form? In order for me to buy into such a claim, I would need to see this usage in ancient texts.

Re: 疆 jiāng, what paleography tells us:

The original form was 畕. Two fields to represent "the border between fields." Later, 一s were added 畺 to emphasize the notion of border. 弓 gōng was added for sound. Then 土 "dirt; earth" was added to emphasize that the meaning of this character has to do with places.

Note that one of the origins of j- in Mandarin is an older g-. Same relation as 江 jiāng and 工 gōng or how 講 is pronounced jiǎng in Mandarin and góng in Cantonese (Cantonese retains older pronunciation in this case).

See how simple and concrete each step is? Two fields to represent "border between fields." Lines added to reinforce the notion of "border." Adding a sound component. Adding "dirt; earth" to emphasize meaning is related to places. All very concrete and all very related to sound and meaning representation.

Last edited:

Ash

进士

I looked up the author of this book and she seems to be genuinely interested in helping people learn Chinese, but just doesn't have the proper training in paleography. I really hope that our dictionary can become a tool for researchers like this that want to produce better pedagogical methods, but based on an actual, reliable understanding of how characters actually work instead of making up stuff out of thin air. I looked the book up on amazon.com hoping to be able to read parts of it. Would you be willing to post (maybe take a picture of or whatnot) the bibliographies for chapters 5 - 8? That's where it'll tell who's ideas she's using for her analyses. If you don't want to do that, could you email them to me at ash@outlier-linguistics.com?That's why I tend to be very cautious when I read explanations as the following (taken from Post-Lingual Chinese Language Learning. Hanzi Pedagogy Palgrave Macmillan UK (2017), p. 69):...

"

Good morning, Ash.If you don't want to do that, could you email them to me at ash@outlier-linguistics.com?

I've just sent you this book in PDF format.

Good luck, and good health!

pdwalker

状元

I just noticed that the screenshots for the outlier in the pleco addons (iOS) don't show the latest features.

It might be a good idea to update those screenshots, especially using one that shows the red overlays.

(Or i am not seeing it on my phone because I've previously purchased the dictionary)

Good screenshots help me say yes to purchasing new dictionaries.

It might be a good idea to update those screenshots, especially using one that shows the red overlays.

(Or i am not seeing it on my phone because I've previously purchased the dictionary)

Good screenshots help me say yes to purchasing new dictionaries.

Last edited:

Ash

进士

Sorry for the late response, but yes, that is a very good suggestion. John sent new screenshots to Pleco today, so hopefully, they'll go out with the new update.I just noticed that the screenshots for the outlier in the pleco addons (iOS) doesn't show the latest features.

It might be a good idea to update those screenshots, especially using one that shows the red overlays.

(Or i am not seeing it on my phone because I've previously purchased the dictionary)

Good screenshots help me say yes to purchasing new dictionaries.